[When I began this Blog, I had recently read the book by Griffiths cited below. It was an interesting read but shed very little light on the writer – even his age was simply a crude guess. In the event a close reading of the book revealed a few hints, each of which in turn led to further items of information and so on. Now the outline of the life is quite extensively filled-out and the range of interests and versatility of the man, are notable. Further research will doubtless reveal more – including, one hopes, the source and date of his M.D. This draft text consciously includes my ‘workings’.

A second Blog will explore the content of his book and its contribution to research on 17th to 19th century ‘Syria’. DLK. 20240221].

In 1805, a book was published in London and Edinburgh under the title Travels in Europe, Asia Minor, and Arabia. The sole naming of the author is on the title page:

J. Griffiths, M.D.

Member of Royal Medical Society of Edinburgh

And of Several Foreign Literary Societies

Several modern references expand the initial as John or Julius and one as John Julius (below); his surname in references to him is rendered both as Griffiths and Griffith. Fortunately, the published records of the Royal Medical Society of Edinburgh record the enrolment as an Ordinary Member of ‘Julius Griffith (sic), M. D.’ on 14 December 1804 – just a few months before the publication of his book (Anon. 1906: 51). Griffiths himself published a translation of a testimonial the same year (Lavallee 1804) in which he gave his name as Griffiths and his book the following year also has the ‘s’. It seems, however, that he began to drop the ‘s’ and – as we shall see, his children certainly did. Other people cited him with or without the ‘s’ or even both in the same reference.

Fig. 1: Etching (from a painting?) of Julius Griffiths (from Griffiths 1805: Flyleaf)

The testimonial referred to above adds that (Lavallee 1804: 4-5):

Mr. J. Griffiths was born in England, in the year 1765; and received a liberal education, during seven years, at Merchant-Taylors’ School, …; from whence there are annually elected, for the College of St. John, Oxford, certain of the head-scholars, in proportion to the vacancies which may be open, but which rarely exceed three: In the eighth year of Griffiths’s education, he was entitled to this honorable distinction; but, not availing himself of it, he soon afterwards determined upon travelling on the Continent.

The year of birth is incorrect: Griffiths’ school record gives his precise birth as 12 July 1763.[1] No place of birth is recorded but – under 1803) when he encountered him, the diarist Joseph Farington recorded that Julius Griffiths was (Cave/ Farington 1979: 1826): ‘… the Son of a Hop Merchant who lived in the Borough of Southwark,…’. A ‘John Griffiths’ is listed in the Kent Directory for 1794 as a ‘Brandy & Hop Mercht. 29, Pudding Lane’ – north of the Thames but perhaps the father or brother of Julius Griffiths. A ‘Griffiths Wharf’ existed as a placename in London into the early 19th century (****). Although unproven, it would make sense if Julius Griffiths was in a family trading (to France?) in brandy and familiar with shippers; probably based in London.

‘Residence in Southwark would broadly accord with his enrolment at Merchant Taylors’ School while Pudding Lane is just 300 m from the school.’Residence in Southwark would broadly accord with his enrolment at Merchant Taylors School while Pudding Lane is just 300 m from the school.

In the 1770s Merchant Taylors’ School was a day school in a grand building in Westminster (now demolished). The School provided an education in Hebrew, Greek, Latin and in Drama. Although it decided in this very period not to introduce teaching in Mathematics – that would surely have appealed to Griffiths (below), it did introduce Geography ‘to enable the boys to read the ancient historians.’

In his book, Griffiths refers to his Latin instruction which involved a pronunciation thought wrong and at times unintelligible by educated people on the Continent (and in Scotland) (1805: 17-18). Apart from the French in which he was evidently fluent and the Italian which was the lingua franca of much of the Mediterranean and certainly of traders, some years later he was also competent in German (below).

The records of Merchant Taylors’ School record ‘a Julius Griffiths, born 12.7.1763 who attended the school between 1771-1778, spending five terms in the sixth form.’ Lavallee (above) observed that Griffiths did not proceed in an eighth year to one of the scholarships for Merchant Taylors’ pupils at St Johns College in Cambridge. There is evidently a gap after 1778 and before he began the eastern travels recounted in his book.

A record of the payment for an apprenticeship indenture dated 10 June 1779 for a Julius Griffiths to ‘John Gunning Surgeon of London’, may be our man entering on medical training, aged not quite 16. Two documents record a ‘Julius Griffiths House Surgeon’ giving evidence about a corpse brought into St George’s Hospital in Westminster (LondonLives[2]). Gunning was the Surgeon there from 1765 till 1798. There is no evidence that Griffiths completed his apprenticeship and in his book, while in Anatolia, Griffiths twice records being asked if he was a physician and denying it (Griffiths 1805: 293 and 296). He plainly had a keen interest in hospitals and medicine as is evident in his reports on his observations in Italy (e.g. Griffiths 1805: 28-31).

In February 1802 the testimonial by Lavallee (1804: 4-5) makes no mention of medical training or a qualification and Griffiths’ own dedication (dated April 1803) in the translation is likewise silent, describing himself only as ‘Esq(uire)’ (Lavallee 1804: Dedication). By 1804, however, he is describing himself to the Medical Society in Edinburgh as a physician (above). A decade later, in 1814-5 and by then living in Vienna, he was described by his long-time friend Auguste de la Garde-Chambonas (1902: 248):[3]

At eight the next morning I was at the prince’s with Griffiths, who, having all his life made the science of healing a particular study, felt only too pleased to assist one he liked so well.

A few years later, by then living in Brussels but about to return to Vienna, The Times newspaper reported (21 January 1817) that ‘From Vienna we learn that John Julius Griffith, an English physician, …’. The name is mangled but it is clearly our Griffiths.

We may guess that Griffith had early recognised the desirability of travellers having medical skills and at some point after 1786 and perhaps precisely c. 1802-4 (above), had undertaken formal study. Given his linguistic skills and residences in France, Belgium and Austria, the studies were not necessarily in Britain. However, the degree of Doctor of Medicine (M.D.) implies an award from one of the old Scottish Universities – Glasgow, Edinburgh, Aberdeen and St Andrews, which would accord with his membership of the Royal Medical Society of Edinburgh (above). No record has yet emerged.

Griffiths apprenticeship seems to have been cut short in 1782 or soon after when – aged c. 19/20, he went to France then, soon after, set off on his great journey (1805: 2):

The liberality of an indulgent father had already permitted my residence in France for two years; when, soon after my return to England, I accidentally met with an acquaintance of my earlier years, who was then captain of a ship bound to Italy and Smyrna. So favorable an opportunity of gratifying my desire to travel renewed it with augmented force; and estimating all inconveniences or sacrifices as trivial, in comparison to the satisfaction which I promised myself, I embarked at Gravesend, in June 1785, for the Mediterranean.

As the war with the American colonists and their French allies had ended with preliminary articles of a peace treaty with France signed 20 January 1783, at Versailles (and final treaty on 3 September 1783), we may suppose the two years Griffiths had been in France were from c. Spring 1783 to Spring 1785. Where Griffiths went in France during those two years is unknown, nor for what purpose. That would make him not quite twenty two years old when he embarked at Gravesend in June 1785 at the start of his eastern travels. It would be interesting to know the identity of ‘an acquaintance of my earlier years’ who was by 1785 was the captain of a newly built ship being sent to Smyrna.

Fig. 2: Sketch of the harbour and Thames at Gravesend as seen by the artists Thomas and William Daniell in 1785 (published 1810), a few months before Griffiths sailed from there. At least one of the Daniells met Griffiths in India (below).

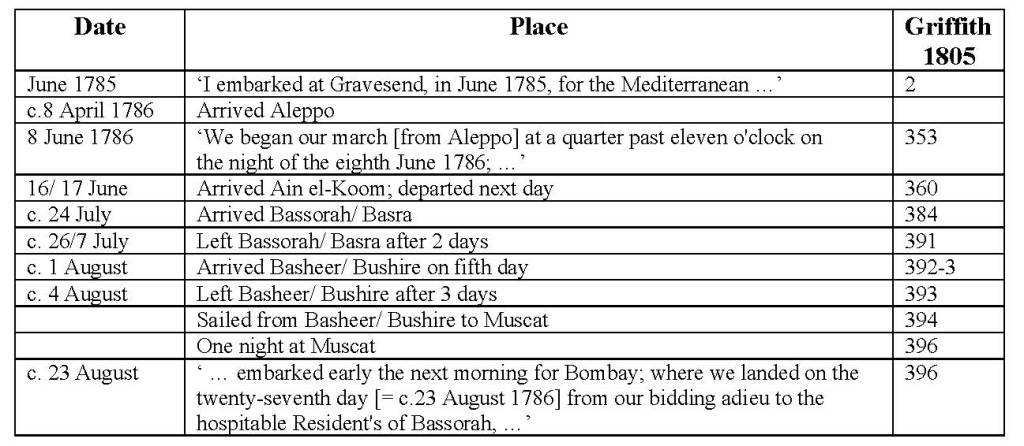

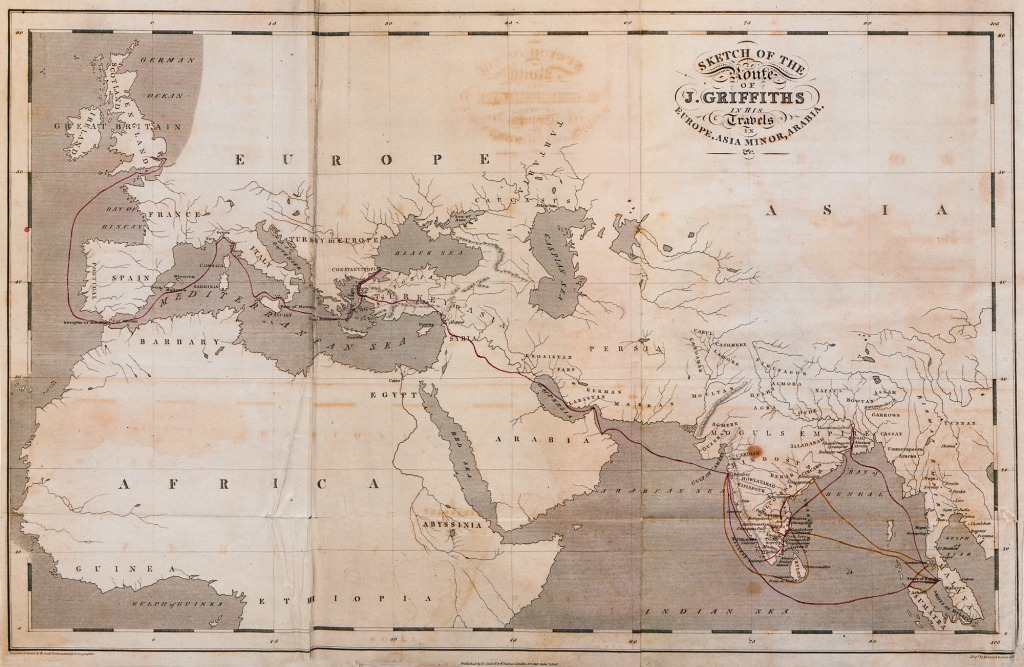

The first 14 months of Griffiths’ eastern journeys are well-known from his book. There is no obvious destination for his travels beyond – perhaps, ‘India’. He started at Gravesend in June 1785, by sea to Mediterranean France and Italy, onwards by sea to Smyrna, to Constantinople and back to Smyrna. Then he went overland through much of Anatolia to take passage from Karatas across the entrance of the Bay of Iskenderun to Suedia on the Syrian coast, near the mouth of the R. Orontes. He continued overland to Aleppo then, after two months and an aborted plan to go north to Georgia in the Caucasus, he undertook – in high summer, the hard and dangerous desert route to Basra. After a stay at the latter, he went on to the Gulf at Bushire, sailed to Muscat and finally reached his destination, Bombay. There are few dates, but the arrival in Bombay can be calculated as c. 23 August 1786, about 14-15 months after his departure from London (Table **).

Table 1: Griffiths’ itinerary to Bombay

His book breaks off with his arrival in Bombay (1805: 396):

We remained here only one night, and embarked early the next morning for Bombay; where we landed on the twenty-seventh day from our bidding adieu to the hospitable Resident’s of Bassorah, and where I found an ample recompence (sic) for all my fatigues in the society of the most affectionate of brothers.

This is the first and only reference to any siblings. A John Griffith was an officer of the East India Company army at Bombay. This may be the same John Griffith – one of twins, baptised in Peterborough by John and Mary Griffiths in March 1762, eighteen months before the same parents baptised a Julius Griffiths on 9 October 1763. Connections are yet to be established.

INDIA

Griffiths’ book ends with his arrival in Bombay and he seems not to have published any further travel books and no manuscript travel journals are known. However, he had stressed at the outset of the book that much more was to follow (1805: xi-xii):

The Countries referred to in the present Volume form a very small portion of those which I have visited; and detained me, comparatively speaking, a very short time: … It is in the various latitudes of India that I have principally travelled, and to the complicated interests of that magnificent country, that I have principally devoted my humble talents for investigation.

Although France, Denmark, Portugal and the Dutch Republic had ‘factories’ in India, by the 1780s the largest foreign presence was the Honourable East India Company with principal centres at Bombay, Madras and Calcutta. Griffiths does not say anything about the extent or duration of his travels in India but there are a few clues. At one point in his book (1805: 393-4) he recounts meeting again, three years later at Calcutta, someone encountered first at Bushire before he sailed to Muscat (above). More useful is the map included in the book which shows not just the route to Bombay but extensive travel in and around India, notably to Pondicherry and places nearby, and to Calcutta and up the Hooghley River as far as Murshabad (Fig. **). The map also records a voyage round Sri Lanka and eastwards to Aceh at the top of Sumatra, and to two places on the western side of the Thai-Malay Peninsula: ‘Prince of Wales Island’ – now Penang Island, which he evidently visited at least twice: once from Calcutta and once from Pondicherry; and Junk/ Salang/ Thalang, now Phuket, Thailand. None of the latter is included in the book and it may be Griffiths intended a second volume for which this map would be suitable.

Fig. 3: Griffiths’ map of his travels to and around India and the Malay Peninsula.

Fortunately, Griffiths had evidently provided Lavallee with more extensive accounts of his travels and the Frenchman included a summary in his testimonial for ‘Julius Griffiths, Esq., an English traveller’ (1804: 15-16):

Here [Bombay], it may he said, he again found his country; and the presence of his countrymen added new charms to the interesting observations, which he made in all the various ports and settlements of the Malabar and Coromandel coasts, without, in any degree, damping the ardor of his inquiry. Penetrating into the interior of the peninsula of India, he travelled through the kingdoms of Travancore and Tanjore, the possessions of the Nabob of Arcot, and, climbing the immense and towering Ghauts, proceeded through the beautiful province of Mysoor, almost as far as Seringapatam, the capital of Tippoo Sultaun, but where the English authority now governs; as the descendent and heir of the ancient royal family of Mysoor has been placed by the English upon the Musnud, on condition of becoming their tributary. Our traveller then passed through part of the Cuttack country, the lower latitudes of Bengal, visited Calcutta, and all the settlements upon the river Hoogly, until he arrived at the venerable city of Moorshedabad.

He afterwards examined the famous Island of Ceylon, both internally and externally; an undertaking of no common kind at that time; proceeded to Sumatra, in the Streights (sic) of Malacca, and visited many of the islands dependent upon the kingdoms of Siam and Queda, particularly Pulo Penang and Junk Seilan, upon which are considerable commercial establishments, and where many English, Chinese, Scamese (sic), and Malay inhabitants reside.

At this point we can add what was recorded by Joseph Farington several years later, after meeting someone who had known Griffiths in India (Cave/ Farington 1979: 1825-6 (Friday 3 September 1802):

Today I met Captn. Barclay formerly in the East India Service. He spoke to me of Mr Griffith (sic) … He said Griffith is the Son of a Hop Merchant who lived in the Borough of Southwark, – that He was a Speculator, a Man of much adventure and had been Master Attendant at a Settlement in the East Indies: That He is about 35 Years of age and is speculating now in various ways in hopes of making a fortune: That He is a Man of abilities, but irregular.

What was meant by ‘Master Attendant at a Settlement in the East Indies’ is preserved in records relating to the earliest colonization of Penang (Sandhu 1969: 132-3; cf. Augustine 2021: np):

In June 1787 an enterprising Calcutta resident named Crucifix suggested that Penang might be ‘a convenient dumping ground’ for convicts who, he considered, should be given to him for a term of some years and made to work for his private profit on the land. But this was not accepted by the government. The reasons for the refusal are unstated but were in all probability connected more with the timing and the terms of the offer than concern over the principle of transportation, as this mode of punishment was already in vogue in England. This assumption appears to be borne out by the fact that in January 1789 – by which time transportation to Penang as a form of punishment had been finally decided upon – the Governor-General [= Cornwallis] gave permission to one Mr Julius Griffith to transport twenty dacoits from Bengal to Penang. He could employ them there for a period of three years for his own profit with certain conditions relating to the treatment.” However, whether Julius Griffith did in fact bring these convicts to Penang is unknown, …

Presumably the surviving manuscript records relating to this colonization of Penang are capable of shedding more detailed light on the extent and duration of Griffiths’ involvement (Sadhu 1968: 132 n. 4). As Cornwallis was also very active in extending Company control in India itself, it may be Griffiths was involved there, too. Certainly Griffiths himself, is credited with saying in relation to a ‘Mr Raily’ he met in Vienna in 1814-5 – ‘The first time I met him was at Lord Cornwallis’s in India …’ (Garde-Chambonas 1902: 288). In a second Diary entry, Farington again refers to Griffiths as a ‘Speculator’ and adds in relation to Griffiths’ business arrangement with Maria Cosway (below) (Cave/ Farington 1979: 1908-9 (Friday 8 October 1802):

‘Mr Fitzhugh & Daniell who know (sic) Griffith in India have cautioned her against him. I told her He had been represented to me as a Speculator & in a way that cause me to think she should be upon her guard.’

The artists, Thomas Daniell (1749-1840), and his nephew William Daniell (1769-1837) had sailed from Gravesend in April 1785, just a few weeks before Griffiths. They went first to China but then to India – arriving in Calcutta early 1786 and leaving from Bombay in May 1793, and spent several years touring extensively. Where and when they met Griffiths is unknown but it would seem they were at least wary of him as a businessman (below).

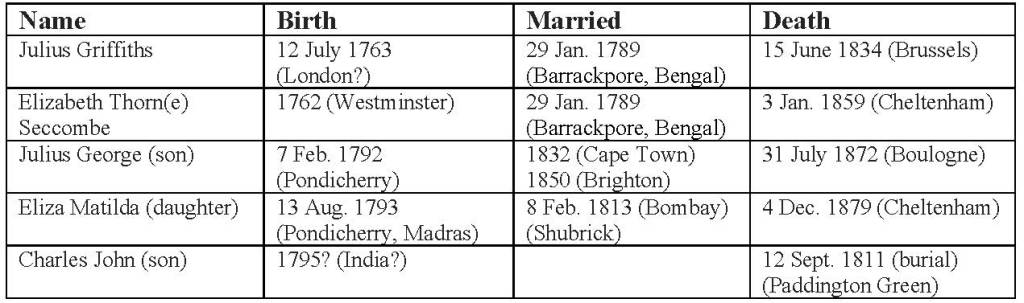

How long Griffiths remained in the Indies is unknown. Fortunately there is a record of his marriage at Barrackpore, Bengal, to Elizabeth Thorne Seccombe on 29 Jan. 1789. Elizabeth had been born in London in 1762. On 7 February 1792 their son Julius George Griffith was born at Pondicherry, a French factory on the coast c. 130 km south of Madras. In 1793 it was brought under British control during the wars with Napoleonic France. A daughter, Eliza Matilda Griffith was also born there on 13 August 1793. In 1795 a son, Charles John Griffith was also born in India but it is not known where. In short, Griffiths remained in India until at least 1794. Both sons are recorded as enrolling at Harrow in the September-Christmas 1802 term and leaving in 1807 and 1811 respectively. Julius George enrolled in the Artillery on 27 May 1810 and rose to the rank of General (below). Eliza Matilda was in London on 1 April 1812 then – in unknown circumstances, at Bombay on 8 February 1813[4] where she married and had six children (with living descendants) (below). Charles John died in London in 1811, just 17 years old.

It may be the Griffiths’ marriage did not endure. Certainly Elizabeth is not mentioned thereafter in connection with Griffiths. Nowhere in Lavallee’s biography is there any mention of a wife and children and the same is the case with Garde-Chambonas both in his letters to Griffiths (below) and his report of residing with him in Vienna. However, Elizabeth was certainly still alive and is recorded in England later in life, lived to 97, and died in 1859, having outlived Griffiths by 45 years (below).

Although Griffiths has left no known record of his travels in India and – ultimately, back to England, apart from the route on his map (Fig. **), he evidently gave Joseph Lavallee an account which the latter included in his testimonial to the Philotechnic Society of Paris (1804: 15-17):

Here [= Bombay], it may he said, he again found his country; and the presence of his countrymen added new charms to the interesting observations, which he made in all the various ports and settlements of the Malabar and Coromandel coasts, without, in any degree, damping the ardor of his inquiry. Penetrating into the interior of the peninsula of India, he travelled through the kingdoms of Travancore and Tanjore, the possessions of the Nabob of Arcot, and, climbing the immense and towering Ghauts, proceeded through the beautiful province of Mysoor, almost as far as Seringapatam, the capital of Tippoo Sultaun, but where the English authority now governs;…. Our traveller then passed through part of the Cuttack country, the lower latitudes of Bengal, visited Calcutta, and all the settlements upon the river Hoogly, until he arrived at the venerable city of Moorshedabad.

He afterwards examined the famous Island of Ceylon, both internally and externally; an undertaking of no common kind at that time; proceeded to Sumatra, in the Streights (sic) of Malacca, and visited many of the islands dependent upon the kingdoms of Siam and Queda, particularly Pulo Penang and Junk Seilan, upon which are considerable commercial establishments, and where many English, Chinese, Scamese (sic), and Malay inhabitants reside.

At length, after so long an absence, the desire of once more beholding the borders of the Thames induced, him to embark on board a neutral ship, which touched at the happy Isle of France [= Mauritius], where he obtained permission, although in time of war, to remain three months; then doubling the Cape of Good Hope, he, after a passage of three months and a half, safely landed at Hamburgh (sic).

Since his return to Europe, he has travelled through a considerable part of Germany, Portugal, Wales, and England, and has again quitted his own country to revisit the French.

No dates are provided but we have to place his return to Europe (Hamburg in fact), after 1795 when he was still at Pondicherry (Table **). Interestingly, on the long sea journey home round Cape of Good Hope, he was allowed to remain three months in French Mauritius, perhaps in part at least as a French-speaker, or was it during the reduced activity of the start of the Peace of Amiens? (The Island became British in 1810). The final words evidently refer to his presence in Paris during the Peace of Amiens (27 Mar 1802 till 18 May 1803) when he encountered Maria Cosway (below) and was proposed by Lavallee for election to the Society. It may be noted that Griffiths was in Paris at the same time as the (1st) Marquess Cornwallis (1738-1805) who was negotiating the Treaty. He had known him some years before when Cornwallis was Governor-General of India (1786-1793) (above).

LATER TRAVELS

Griffiths evidently travelled much more widely before he is found in Vienna in 1814-15. To Hamburg, we can add Portugal (above) and in the text quoted above, Garde-Chambonas went on to say that Griffiths had encountered Raily (1902: 288):

… in Hamburg, in Sweden, in Moscow, in Paris at the period of the Peace of Amiens, when he told me he had just arrived from Spain. And now, he is here in Vienna, …

The Peace of Amiens lasted from 27 Mar 1802 till 18 May 1803 and it is in this period Griffiths is found involved in an enterprise in Paris with the artist Maria Cosway (below). If the list is in chronological order, then Griffiths’ travels after India need to fit into a narrow period before 1802/3 and when the countries in question were largely engaged in wars. He evidently maintained a home in England and was often there.

As an aside, the same Garde-Chambonas who published his Recollections of the Congress of Vienna many years later, had already in 1824 published – in French then German translation, the voluminous letters he had sent while travelling: Voyages de Moscou à Vienne, par Kiow, Odessa, Constantinople, Bucharest et Hermanstadt, subtitled, ou Letres Addressés à Jules Griffith (1824 and 1825). It is only at the start of the first letter that he addresses him by name (1824: 1):

Today is May 1st [1811], my dear Griffith (sic); I am leaving Moscow, returning from a walk where I was able to appreciate all of Moscow’s luxury, and which reminded me of the most remarkable things I have seen of this type.

In the Avant-Propos, however, without naming him, he explained (1824: vii):

Separated from a friend whose affection a thousand proofs of attachment had made me very dear, we made up for his absence by writing to each other as often as the long distance that kept us apart allowed. When I left Moscow to go to Vienna in 1811, our correspondence was more active, and continued with the detour that I had to take to join him. Traveling this year in England [= c. 1823-4], I found my friend in his family: he had kept most of my letters; I believed their content to be of some interest, and yielding to the requests made to me, I ventured to publish the first collection.

It is clear from this and the considerable number of letters that there was a genuine friendship between the two men, despite the difference in age – Garde-Chambonas was apparently born in Paris in 1783, so 20+ years younger.

As noted, Griffiths seems to have been one of those who flooded into Paris during the respite from war provided by the Peace of Amiens. By 1811 Garde-Chambonas’ Letters (above) imply he is in Vienna. Certainly by 1814-15 he was a long-time resident in Vienna. At that time when rulers, ministers and staffs flooded into the city for the Congress to decide on the fate of Napoleon, France and Europe, prices rose steeply, and Garde-Chambonas was able to take up residence in Griffiths’ home (Garde-Chambonas 1902: 8-9):

… my intimate friend, Mr. Julius Griffiths, who had lived in Vienna for several years, had anticipated my coming, and in his magnificent residence on the Jaeger-Zeill, I found all the comfort which he had transported thither from his own country; both the word and the condition of things it represented being little known throughout the rest of Europe.

Mr. Julius Griffiths, who ranks among the best educated of Englishmen, has made himself widely known in the world of letters by works of acknowledged merit. He has travelled all over the globe, and deserves to be proclaimed the greatest traveller of his time. His social qualities and his lofty sentiments have conferred the greatest honour on the English character outside his native country. His friendship has been for many years the source of my sweetest happiness. I am enabled to confess with gratitude that he was instrumental in convincing me of the mendacity of the precept, ‘not to try one’s friends if one wishes to keep them.’

The two men spent a great deal of time together in Vienna, and Garde-Chambonas recounted several events involving Griffiths some of which shed light on the older man. Most obvious is the extent to which Griffiths was regularly included in social events hosted by some of the aristocratic magnates.

In none of Garde-Chambonas’ references to residing with Griffiths and to their joint excursions is there any reference to Griffiths’ family: his elder son had joined the army in 1810; the younger had died in 1811; and his daughter had married in 1813 and remained in India until at least 1822 when her husband died in Bombay (below). But where is his wife, Elizabeth – had she, too, remained in India with her daughter and six grandchildren?

Table 2: Family of Julius Griffith

GRIFFITHS AS ENTREPRENEUR AND SPECULATOR

Apart from his investment(s) in the East Indies, Griffiths is known for an investment in the arts while in Paris at the time of the Peace of Amiens, when he arranged to invest with the Anglo-Italian artist Maria Cosway (1760-1838). She undertook to make etchings from paintings in the Louvre and from the plate produce albums for sale. A copy of the prospectus reads (quoted by Lyons 2022: 89?):

The plan is to publish by subscription a work, entitled Gallery of the Louvre, represented by etchings, executed solely by Mrs Maria Cosway; with an historical and critical description, in French and English, of all the pictures … and a biographical sketch of each painter, by J. Griffiths, Esq.

The partners fell out and Cosway was given some advice by Farington on handling Griffiths which is illuminating and contrasts with Garde-Chambonas’ affectionate characterization (Farington, Diary, Vol 5, October 8, 1802):

She mentioned to me Her situation with Mr. Griffiths …. It was in Paris that she communicated Her Scheme to Mr. Griffiths who proposed to unite with her in it. A contract was formed and she undertook to supply a Plate of a Compartment one in every Month till the whole shd. Be completed: That He was to undertake the expenses of paper – printing &c & that after all expenses were paid she was to have a third of the profits. Mr Griffith (sic) then announced himself Proprietor of the work & extended the Scheme so far by making letter-press descriptions as to render it very expensive. She has now been twelve months and has not received a shilling on account of the work, & Mr Fitzhugh & Daniell who know (sic) Griffith in India have cautioned her against him. I told her He had been represented to me as a Speculator & in a way that cause me to think she should be upon her guard. She said Griffith had now no objection to her quitting the work which He then wd. have executed by better Artists than she was, …

The end of the Peace of Amiens blocked Cosway’s work in the Louvre and the differences with Griffiths caused the scheme to collapse with little achieved (Lyons 2022: 89-95).[5]

At about the same time, Griffiths was proposed for election to a French technical society and one knowledgeable commentator (below) later observed that the privately printed translation he had made employed a quite novel printing process, again implying an interest in new technical matters (Lavallee 1804: Handwritten comment on p. 1 by the Earl of Buchan).[6]

As noted, Griffiths evidently lived in Vienna for many years – from 1811 or earlier and certainly spanning the Congress of Vienna in 1814-15. However, he fell foul of the Austrian authorities soon after, as reported in the British press (The Times, 21 January 1817 (Column 2):

From Vienna we learn that John Julius Griffith (sic), an English physician, well-known for some learned works which he has published on Asia, and who was forced to quit Vienna in November, 1815, in consequence of incurring the suspicion of a political correspondence with Murat, has transmitted to Prince Metternich a memoir, in consequence of which he received permission to return to Vienna.

Why Griffiths was corresponding with Joachim Murat is baffling. Murat was one of Napoleon’s most brilliant marshals, and had been installed by the latter as King of Naples. He was married to Napoleon’s sister Caroline Bonaparte. After Napoleon’s abdication, Murat had declared war on Austria and attacked it in northern Italy. He was soon defeated and after unsuccessful attempts to remain in power, was captured and executed in Calabria.

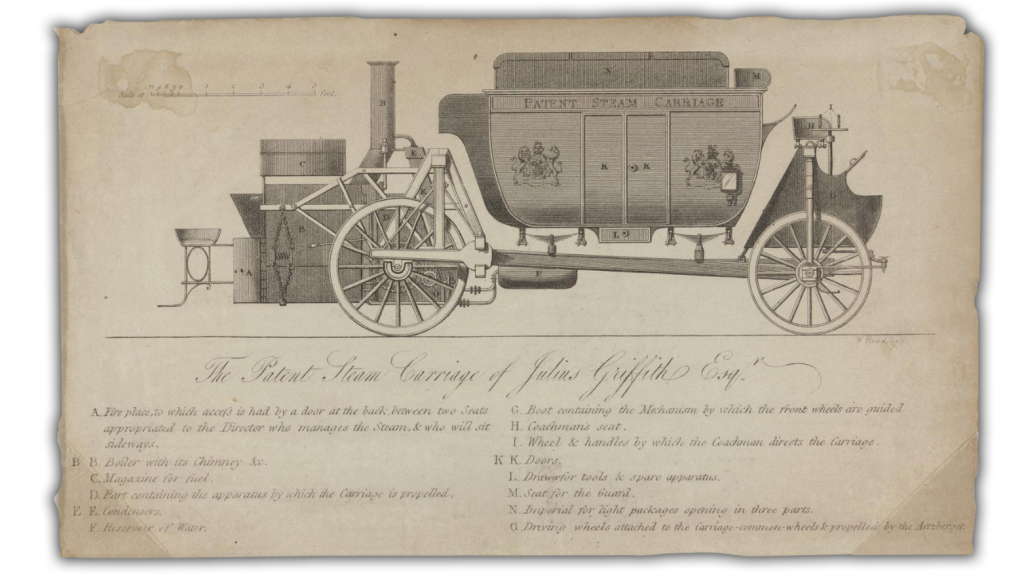

While resident in Vienna Griffith met Johann Arzberger (1778-1835), an Austrian engineer based at the Polytechnic Institute in Vienna from 1816, who had worked on various mechanical technology project including a coal gas plant to power a pioneering project for street-lighting in Vienna. Steam engines were not new, but in about 1820 Arzberger invented a method of converting the steam power in an engine into a drive for the wheels of a road carriage. He seems to have been joined by Griffiths and together they built a protype which ran on roads in Vienna. This first steam-engined road vehicle – just nine years before Stephenson’s ‘Rocket’ took steam-powered locomotion to a railway, seems not to have been developed further (Schmidt-Römer (n.d.): A9). Instead, on 20 December 1821, Griffiths, from a London address, took out a patent for his own development of the Arzberger design – in which he acknowledges previous and external ‘discoveries’ but presents as ‘my invention’:

A grant unto JULIUS GRIFFITH (sic), of Brompton Crescent,[7] in the county of Middlesex, esquire, in consequence of discoveries made by himself and communications made to him by foreigners residing abroad he is in possession of “Certain improvements in steam carriages, and which steam carriages are capable of transporting merchandize of all kinds, as well as passengers, upon common roads, without the aid of horses”; six months.

Fig. 4: ‘The Patent team Carriage of Julius Griffith (sic) Esqr’ (Drawing held by the Henry Ford Museum).

The full Patent (No. 4630) Specification, dated 20 June 1822, exactly 6 months later as required, ran to eight pages and included detailed descriptions keyed to drawings (Griffiths 1822). One of the latter can be seen in the Henry Ford Museum in Detroit (Fig. ***).

Griffiths was open about the origins of an important element of his Steam Carriage, explicitly mentioning ‘John Artzberger of Vienna’ as the inventor of a key part of the mechanism (‘it being an entirely new combination and arrangement of parts’) and that he will thereafter refer to that part as ‘the Artzberger’ (Anon. 1823: 6). He went on to specify what he was laying claim to as ‘my invention’ (Anon. 1823: 8):

I do not intend hereby to claim as of my invention any of the parts of this machine which may have been in use heretofore, but I do hereby claim the suspension of the steam engine boiler and engines upon springs, and the mode of communicating motion therefrom to the carriage wheels by the mediation of the Artzbergers, so that neither the turning of the carriage wheels, independently of the steam engines, nor their balancing movement upon the springs, can prove injurious to the mechanism. Neither do I mean or intend hereby to limit myself to the employment of two steam engines or four carriage wheels, only considering every kind of modification which may appear to me necessary in my endeavours to bring my steam carriages nearer to perfection, as being under the protection of my Patent.

This Griffiths Steam Carriage caught public attention with write-ups in the semi-popular press, not least a lengthy text with illustrations published in The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction (Anon. 1823 (15 February 1823): 241-2) (Fig. **). It was taken up and reported as far away as Tasmania (Hobart Town Gazette and Van Diemen’s Land Advertiser, Saturday 21 December 1822):

Steam Carriage.— Mr. Griffiths, of Brompton, a Gentleman known by his travels in Asia Minor, has, in connexion with a professor of mechanics on the Continent, invented a carriage, capable of transporting merchandize and all passengers, upon common roads, without the aid of horses. This carriage is now building at the manufactory of Messrs. Bramah, and its appearance in action may be expected to take place in the course of the spring. … The usual objections are said to be removed, such as the ascending of hills, securing a supply of fuel & water; and the danger of explosion is to be prevented, not only by the safety valve, but by the distribution of the steam into tubes, so as to render any possible explosion wholly unimportant. …

For over a century and a half, there has been a recognition of the significance and role of this Griffiths Steam Carriage in the development of steam power for traction. Although a model was built, it evidently was ultimately unsuccessful. Nevertheless it came very close to being the first commercial road vehicle and there is modern recognition of the important contribution of Griffiths’ carriage (e.g. Torchinsky 2019).

Fig. 5: Artist’s impression of The Griffith Steam Carriage (Published 1905)

GRIFFITHS’ FINAL YEARS

By 1830 Griffiths was living in the rue Royale in Brussels with his widowed daughter, Eliza Matilda Shubrick. On 25 August 1830 the Belgian Revolution broke out and the revolutionaries took over the city. Royalist troops spent three days (23-26 September) battling (unsuccessfully) to recover control. An account by ‘A Resident’, described events including the following (Anon. n.d.: 125):

Among the principal sufferers from the Royal troops from pillage, were Mrs Shubrick and family, and Dr Griffith who were torn away with menacing rudeness from their residence in the new Rue Royale and conducted beyond the Scaerbeck gate as prisoners. On their return, they found their house stripped of furniture, plate and jewels to the amount of at least 5000 L. – Mr Britten and family who lived in the same street, were also forced away as prisoners, and their house was robbed to a considerable extent.

‘Mrs Shubrick and family’: Presumably some of Eliza’s children were living with her and her father.

In 1833 a printed list of people subscribing their support for the ‘Écoles gardiennes de Bruxelles’ (Anon. 1833: 19), includes ‘Shubrick (Mme) [and] Griffith, rentier’.

Griffiths died in Brussels on 15 June 1834, aged c. 69. He died intestate and it was not till 1849 that his surviving son, General Julius George Griffith (sic), could arrange payment of Death Duty. Presumably his assets were divided between two or more countries. His place of burial is unknown.

As noted above, Griffiths’ daughter Eliza Matilda Shubrick, a widow with six children since 1822, was living with him in Brussels in 1830 and 1833. She evidently moved to England after his death in 1834. She is found in successive censuses living at smart addresses in Cheltenham and listed as a ‘Fund Holder’: in 1841 she is the Head of a household which includes her mother, Griffiths’ widow, who has not been mentioned since their marriage and birth of their children in India. In 1851 Eliza is heading a household still with her mother and with own daughter Mary. All three are ‘Fund Holders’. Elizabeth died in 1859 and in the 1861 census Eliza is heading a household with the now 42 year old Mary, a niece and three very young grandchildren, the children of her son Richard. In 1871, by then 77, she is living in the household of her son-in-law, the Rev. Charles Edward Gibson, M.A. (Trinity College, Dublin) husband of Mary.[8]

Eliza Matilda Shubrick, only daughter of Julius and Elizabeth Griffiths, died in Cheltenham in 1879. She was buried alongside her mother in Trinity Church and both are commemorated by a marble plaque on an inside wall of the church:

In loving memory of Elizabeth Thorn Griffith, widow of Julius Griffith Esq. M.D. who died at Cheltenham 26th Decr. 1859, aged 97. And of Eliza Matilda Shubrick her daughter. widow of Charles Shubrick Esq. of the Bombay Civil Service, who died at Cheltenham Decr. 4th 1879 aged 86. “Looking for the mercy of our Lord Jesus Christ unto eternal life.” Jude.21. Their mortal remains are deposited in a vault beneath this church.

Fig. 4: Plaque commemorating Elizabeth Griffiths and her daughter Eliza Matilda Shubrick, Trinity Church, Cheltenham (Photo: Julia ***).

Julius and Elizabeth Griffiths’ elder and surviving son, Julius George Griffiths, had a distinguished career in the Indian Army, rising to the rank of General of Artillery. A grandson, Richard Shubrick, also became a general and one of their great-grandsons, Richard Ladbroke Shubrick – a grandson of Eliza Matilda Shubrick – also went on to be a general. A son of this last, Captain Richard Brian Shubrick, almost exactly 130 years after his great-great grandfather, Julius Griffiths, had passed through the Dardanelles twice on his first great journey, was wounded at Gallipoli on 28 April 1915, evacuated to a hospital ship offshore but died the same day and was buried at sea.

The biography of Griffiths suggests a man of great energy, some charm, enterprise and ingenuity, though arousing some caution amongst those who knew him in his early adulthood. The travels set out in his book were undertaken as a young man: In France for two years in his late teens then setting off for the East in June 1785, still only about 20 with several years of travel ahead of him in his early and mid-20s. The book was written when he was about 40. It is a ‘good read’, especially for the section treating his months into Syria and Mesopotamia.

[Under Construction]

Table **: Provisional tabulation of the key events and dates in the life of Julius Griffiths

REFERENCES

Anon. (1823) ‘Patent Steam Carriage”, The Mirror of Literature, Amusement, and Instruction, I.16: 241-2

Anon. (1833) Écoles gardiennes de Bruxelles, (no publisher or place of publication stated).

Anon. (1906) General List of the Members of the Royal Medical Society of Edinburgh, Edinburgh (RMSE)

Anon. (n.d.) A Narrative of a Few Weeks in Brussels in 1830. By a Resident, Brussels (Pratt and Barry and Demengeot and Goodman)

Augustine, M. G. (2021) ‘Convict constructors – Indian convicts in south east Asia, Journal of Modern Tamil Research **** [in press?]

Cave, K. (ed.) (1978–84) The Diary of Joseph Farington, 16 vols New Haven and London (Yale University Press)

Garde-Chambonas, A. L. C. de la (1824) Voyages de Moscou à Vienne, par Kiow, Odessa, Constantinople, Bucharest et Hermanstadt; ou Letres Addressés à Jules Griffith (sic), Paris (Treuttel and Würtz)

Garde-Chambonas, A. L. C. de la (1825) Reise von Moskau nach Wien, über Kiow, Odessa, Constantinopel, einen Theil des Schwarzen Meeres, bis Varna, Silistria etc: In Briefen An Julius Griffiths, translated from the French, Heidelbergh (Engelmann)

Garde-Chambonas, A. L. C. de la (1902) Anecdotal Recollections of the Congress of Vienna, London (Chapman and Hall) (Translation of the original)

Garde-Chambonas, A. L. C. de la (1827/ 2016) Sketches of Brighton 1827 by a French Nobleman, English trans., S. Hinton, Brighton (Belle Vue Books)

Griffiths, J. (1805) Travels in Europe, Asia Minor, and Arabia, London (T. Cadell & W. Davies) and Edinburgh (Peter Hill)

Griffiths, J. (1822) ‘Steam carriages. Griffith’s (sic) specifications’, Patent Office (UK), No. 4630

Lavalle, J. (1804) Translation of a Report made to the Philotechnic Society of Paris, respecting Julius Griffiths, Esq., an English traveller, London (Stereotyped and Printed by A. Wilson)

Lyons, H. (2022) ‘Exercising the ART as a TRADE’: Professional Women Printmakers in England, c1750-c1850, Birkbeck College, University of London, Unpublished PhD.

Robinson, C. (1883) A Register of the Scholars Admitted into Merchant Taylors’ School: from A. D. 1562 to 1874, II, Lewes (Farncombe and Co).

Sandhu, K. S. (1969) Indians in Malaya: Some Aspects of their Immigration and Settlement (1786–1957), Cambridge (CUP)

Schmidt-Römer,. H. **** Dampfselbstfahrer im Deutschsprachigen Raum. Eine Chronologische und Alphabetische Übersicht der Hersteller für die Zeit zwischen 1780 und 1950.

Torchinsky, J. (2019) ‘The first bus is way older than you think’, Jalopopnik, June 24, 2019 (https://jalopnik.com/the-first-bus-is-way-older-than-you-think-1835820663)

[1] I am grateful to Mr Jonny Taylor, Archivist at Merchant Taylor’s School for this and subsequent information.

[2] https://www.londonlives.org/search.jsp?form=persNames&_persNames_surname=Griffiths&match_sur=exact&_persNames_given=Julius&match_giv=exact&_persNames_div0Type=CW_ICfile&fromMonth=&fromYear=&toMonth=&toYear=&submit.x=53&submit.y=13

[3] As we will see, Garde-Chambonas authored several books including Sketches of Brighton 1827 by a French Nobleman (1827, 2016)

[4] On 1 April 1812, she was a witness in London to the will of her grandfather, Capt. Richard Secombe, in which he gave his address as ‘Brompton’.

[5] The Anglo-Italian Cosway died and is buried in Lodi southeast of Milan where there is an institute devoted to her art: http://www.fondazionemariacosway.it/en/indexen.html. The project with Griffiths: https://www.lombardiabeniculturali.it/ricerca/?q=cosway+griffiths

[6] Inscribed in two different handwritings on the flyleaf: ‘The pamphlet itself is of small consequence, but the inscriptions on the fly leaf, which are copied below, render it of some consequence in the history of book production.-

“To the Literary Society at Newcastle this early specimen of Stereotype in Britain from their ob. bble. servt. – Buchan.”

“N.B.–This was the first work stereotyped according to the process of Lord Stanhope, the first book printed at a Stanhope Press, and the first book printed on machine-made paper.”

[7] This is presumably Brompton Park Crescent, between Stamford Bridge Football ground and the famous Brompton Road Cemetery. No number is provided but several sources show that his father-in-law, Capt. Richard Secombe, R.N., lived at ‘8 Brompton Crescent’ in 1801, 1804, 1811, 1812 and 1816. It is possible Griffiths inherited the house or was just able to use it as his address in London.

[8] Mary had married at 44, the 34-year old Charles Gibson. They died on successive days in April 1904; they had no children.

David Kennedy

22 February 2024