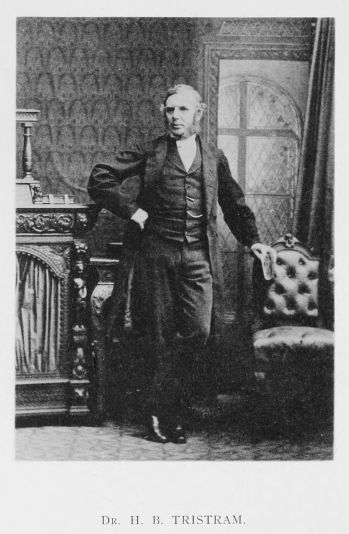

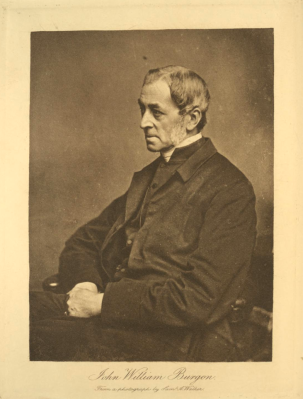

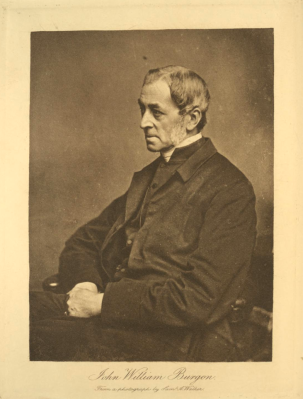

John William Burgon (1813-1888)

Not again! How many more times is that line going to be quoted by everyone who ever writes anything about Petra!

Many people do know the line and a good many could tell you it was from a poem written by John William Burgon (1813-1888) – ‘Dean Burgon’. Much less well-known is that Burgon had never visited Petra – or even the region. In 1845, a very mature student of 32, he entered a poem in the competition for Oxford’s Newdigate Prize. The theme that year was ‘Petra’, a place increasingly ‘in-the-news’ as a steady trickle of bolder western travellers undertook the immensely demanding journey, and wrote about it when they returned home. Burgon won on this – his third attempt, joining an illustrious list of winners over the two centuries including Oscar Wilde, Matthew Arnold and John Buchan.

Photograph of John William Burgon from: Goulburn 1892 John William Burgon late Dean of Chichester: A Biography with extracts from his letters and early journals, Vol. 1 (John Murray: London).

Even less well-known is that Burgon eventually did visit Petra – but not till 17 years later by which time he was almost 50. Two publications offer lengthy and – at the time published, fairly comprehensive lists of western travellers to Petra before 1914. Oddly, neither includes Burgon and a search through even other 19th century writers now easily found for free download, reveals no knowledge of Burgon’s visit …. while endlessly quoting his poem.

The evidence for Burgon’s visit is preserved in a two-volume biography consisting in large part in the numerous letters and other documents he wrote. In 1892 – four years after his death, Edward Goulburn published extensive parts of Burgon’s papers including the spate of letters he wrote in Egypt, crossing Sinai, at Aqaba and at Petra itself, then at Jerusalem after the journey. There is some repetition as he reports the same details to different correspondents, but collectively they allow the reconstruction of this visit.

The impetus for the journey lay with a wealthy lady friend (‘Miss Webb’) Burgon had originally met in Italy. This ‘Webb Party’ set off from Lake Constance for Egypt on 10 September 1861 and there followed the customary extensive cruise down the Nile – in their case as far as the 2nd Cataract. They then set off from Cairo on Saturday 9 March 1862 for Suez, Mt Sinai and reached Aqaba on Saturday 5 April, after four weeks of gruelling travel on camels.

Burgon had hoped they would reach Jerusalem to celebrate Easter there on Good Friday (18th April that year), but their journey took much longer. Instead, they were at Petra for four and half days, having arrived on Wednedsay 16th April 1862 then staying Good Friday, Easter Sunday and leaving on Easter Monday, 21 April.

Burgon reports a generally untroubled visit – unlike the visit just two weeks earlier when one of that group had sent a messenger back hoping to dissuade the Webb Party from proceeding.

As always, Burgon refers to his sketching of ruins and it would be interesting to know if they have survived. He was impressed – 17 years after immortalising the place in verse, he was there. Strangely, he never mentions the poem (at least in the published correspondence). Now he was writing in a letter begun in Petra itself on Easter Sunday (20 April 1862) that it was ‘the most astonishing and interesting place I ever visited, and may well stand alone.’ He remarks on the ‘sandstone cliffs … in colour unrivalled’ but goes on, however, to admit: ‘… there is nothing rosy in Petra, by any means’! A puzzling remark given the immense range of rosy colours one does see at Petra.

On again through the Wadi Araba to Hebron, where they stayed two days, before reaching Jerusalem on Tuesday 29 April 1862. According to Burgon, they had by then been travelling with camels for 50 days. Burgon fell ill in Jerusalem and had to miss the subsequent journeys the rest of the Webb Party made, including the trip east of the Jordan Miss Webb had been planning before they left Egypt. He eventually moved on to Jaffa in a jolting litter drawn by mules, and had to be carried bodily onto a boat which took him to Beirut. Very ill there, he was attended by doctors and prescribed various medicines, remarking in one letter home: “How can a man be taking 6 gr. of quinine per day, and three wine glasses of tonic, with wine, pale ale, and solid food at 9, 1 and 5, without being strengthened?” Perhaps the treatment as much as the illness was the cause of his ‘indescribable languor, and faintness.’

He spent all of June recovering in Beirut before catching a steamer to Marseilles, arriving home on 18 July 1862.

The Webb Party consisted of Miss (Elizabeth Frances) Webb (a niece of Sir John Guise), of Chesham Place (Belgravia), her cousin Miss Frances (‘Fanny’) Guise, their two maids, Captain (RN Retd) and Mrs Bayley and Burgon himself. Captain Bayley is especially interesting – while Burgon sketched, he was taking photographs, over a hundred on the Nile alone, says Burgon.

It is surprising that the visit by Burgon of all people is known to so few. But there is another little mystery to be pursued. While at Aqaba, Burgon reports giving Sheikh Mohammad, the Alawin beduin chief who is to lead them on to Petra, “dear Charles’s message to his father, and said how sorry he would be to hear that Sheik Husseyn is dead”. ‘Charles’ is one of Burgon’s regular correspondents and it was to his home he went to convalesce after returning to England. Charles Longuet Higgins (1806-85) is in fact Burgon’s brother-in-law, married to his sister Helen Eliza. Research is at an early stage but happily Burgon himself subsequently published a short biography of Charles Higgins in his book Lives of Twelve Good Men. In it he reports that Charles Higgins and his brother Henry, and a companion Mr de Grille, “… struck across the desert from Cairo for the Convent of S. Catharine, and entered the Holy Land by way of Hebron, – taking Petra and Mount Hor in their way. … The travellers succeeded in their object, which was to reach Jerusalem (April 8th [1848]) in ample time to witness the solemnities of Holy Week and Easter.” The date is early for visitors to Petra and the visit is otherwise unknown. Indeed, until now the only known visitor to Petra that year is the enigmatic ‘R W G 1848’ from a graffito scratched on the wall of the Khazneh. We may now (perhaps) resolve that puzzle too – ‘R W G’ is probably R W de Grille, though who he is remains (as yet) a mystery …

– DLK

– Article originally appeared on the APAAME blog, reproduced with permission.